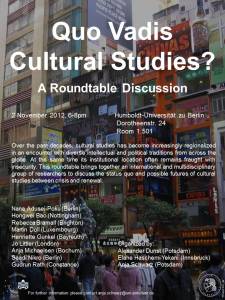

A Workshop and Public Roundtable Discussion on 2  November 2012

November 2012

at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin

Has cultural studies, as Michael Berubé recently argued, “lost its bearings”? In an essay published in the Chronicle of Higher Education (2009), Berubé looks back at the grand hopes sparked by the arrival of cultural studies to the US-American academic scene in the early 1990s and poses a set of rhetorical questions: “[H]as cultural studies transformed the disciplines of the human sciences? Has cultural studies changed the means of transmission of knowledge? Has cultural studies made the [American] university a more egalitarian or progressive institution?” He arrives at the devastating conclusion: “[S]adly, no. Cultural studies hasn’t had much of an impact at all.” While cultural studies has made some inroads into English departments, Bérubé regards its influence on such disciplines as sociology, psychology, economics, political science, and international relations as negligible. He attributes the discipline’s persisting marginality to the failure of cultural studies scholars to distinguish their academic project explicitly from a cheery “Pop culture is fun” approach – a development that already prompted Stuart Hall to complain that “I really cannot read another cultural-studies analysis of Madonna or The Sopranos.”

Further to this harsh critique of cultural studies’ current disciplinarity and methodology by two of its most prominent advocates, the international success story of cultural studies has equally engendered insecurities regarding the intellectual and institutional location of the field. While initially closely linked to Britain and the Birmingham Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies, cultural studies has become increasingly regionalized over the past decades. In this process, practitioners within and beyond academia have transformed cultural studies in the encounter with diverse intellectual and political traditions from across the globe, adapting a theoretically-inflected practice to the demands of regional and institutional contexts from Africa to Asia, Australia to Latin America, and across Europe and North America. But can the resultant local practices still be subsumed under the umbrella of cultural studies?

We would like to answer with a tentative ‘yes’, and rather than accepting Berubé’s diagnosis of cultural studies’ demise, we want to take the current insecurities as instances of the field’s pronounced self-reflexivity. After all, cultural studies has almost always been in crisis, and a methodologically and politically self-reflexive ‘open-endedness’ has characterized the project from the start. This has also meant that discussions about what constitutes good and bad practice have been part and parcel of its history. Taking this most recent eruption of such debates as a prompt, we would like to ask (once more):

- What does it mean to practice cultural studies today?

- What relation exists between cultural studies in the tradition of the Birmingham school and the diverse practices of contemporary cultural studies in its multiple locations?

The one-day workshop invited early-career researchers and established academics to discuss the status quo and possible futures of cultural studies in relation to their current work. In the evening, a public roundtable discussion will examine the current multiplicity of cultural studies approaches in a globalized academic landscape, inviting speakers to reflect on the disciplinary status of the field in ways that go beyond the current discourse of crisis.

Position papers of ten-minute length to be presented at the workshop should address either or both of the following two avenues of enquiry:

1: The (inter-)disciplinary of cultural studies

- What are the methodologies that can help renew the critical import of cultural studies?

- How is the understanding of cultural studies as a discipline (in crisis) related to academic practices in affiliated fields such as gender, postcolonial, trans, queer and disability studies?

- How can we evaluate narratives of crisis, and the futurity of specific (inter-)disciplines, in the context of the corporatization of the academy?

2: The multiplicity of cultural studies

- How can the intellectual traditions and methodologies of regional approaches contribute to and intervene in a cultural studies that often remains characterized by an Anglo-American bias?

- What potential synergies or contradictions exist between cultural studies as practiced across the Global South? How can sustained dialogue and debate between these practices contribute to the larger political project of de-colonization?

- What would it mean to develop a transnational, or even global, cultural studies? And what is the relation between such internationalization and the global expansion of British, American and Australian universities?

Participants of the Round Table were: Nana Adusei-Poku (Rotterdam), Hongwei Bao (Nottingham), Rebecca Bramall (Brighton), Martin Doll (Luxembourg), Alexander Dunst (Paderborn), Henriette Gunkel (London), Elahe Haschemi Yekani (Flensburg), Jo Littler (London), Anja Michaelsen (Bochum), Saadi Nikro (Berlin), Gudrun Rath (Linz) & Anja Schwarz (Potsdam)